F1 Tech | What could be an explanation to Leclerc's problems in Hungary?

20:00, 05 Aug 2025

Updated: 08:52, 06 Aug 2025

1 Comments

The Hungarian Grand Prix delivered an exciting race, with Norris successfully executing the one-stop strategy to win. At the same time, Leclerc's performance was hindered by “mysterious” issues that ultimately cost him a potential victory, despite securing a majestic pole on Saturday. Let’s try to analyse what’s behind the two contenders’ performance during last weekend.

McLaren arrived in Budapest with high hopes that the Hungaroring would have perfectly suited their car: the presence of medium speed and very long corners should have exploited the MCL39’s great aero-mechanical balance, which contributes to making this car the strongest on these layouts.

For this weekend, the team decided to adopt a maximum downforce rear wing on both cars: as highlighted by the picture below, the rear wing spec chosen is characterised by a mainplane with a leading edge that follows a straight path for most of its length. At the attachment point to the endplates, the profile shows a slight oblique inclination to improve flow separation in this critical area of the airfoil.

Furthermore, the mainplane was characterised by a very pronounced chord along its entire length, precisely to ensure maximum vertical thrust on the narrow and twisty Hungarian Circuit. As for the DRS flap, it has a modest chord but much less than that of the mainplane, to ensure good efficiency with the DRS open.

Mclaren's rear wing and beam wing choice for the Hungarian GP

To better suit the track’s characteristics, the team decided to adopt a double-element beam wing on both cars, with the lower element characterised by a massive chord, to work like an extension of the diffuser ceiling, helping the flow extraction and maximising downforce and with the upper element having a beam shape, almost horizontal, to better manage the low pressure area generated at the back end of the car, producing downforce but without penalising the top speed.

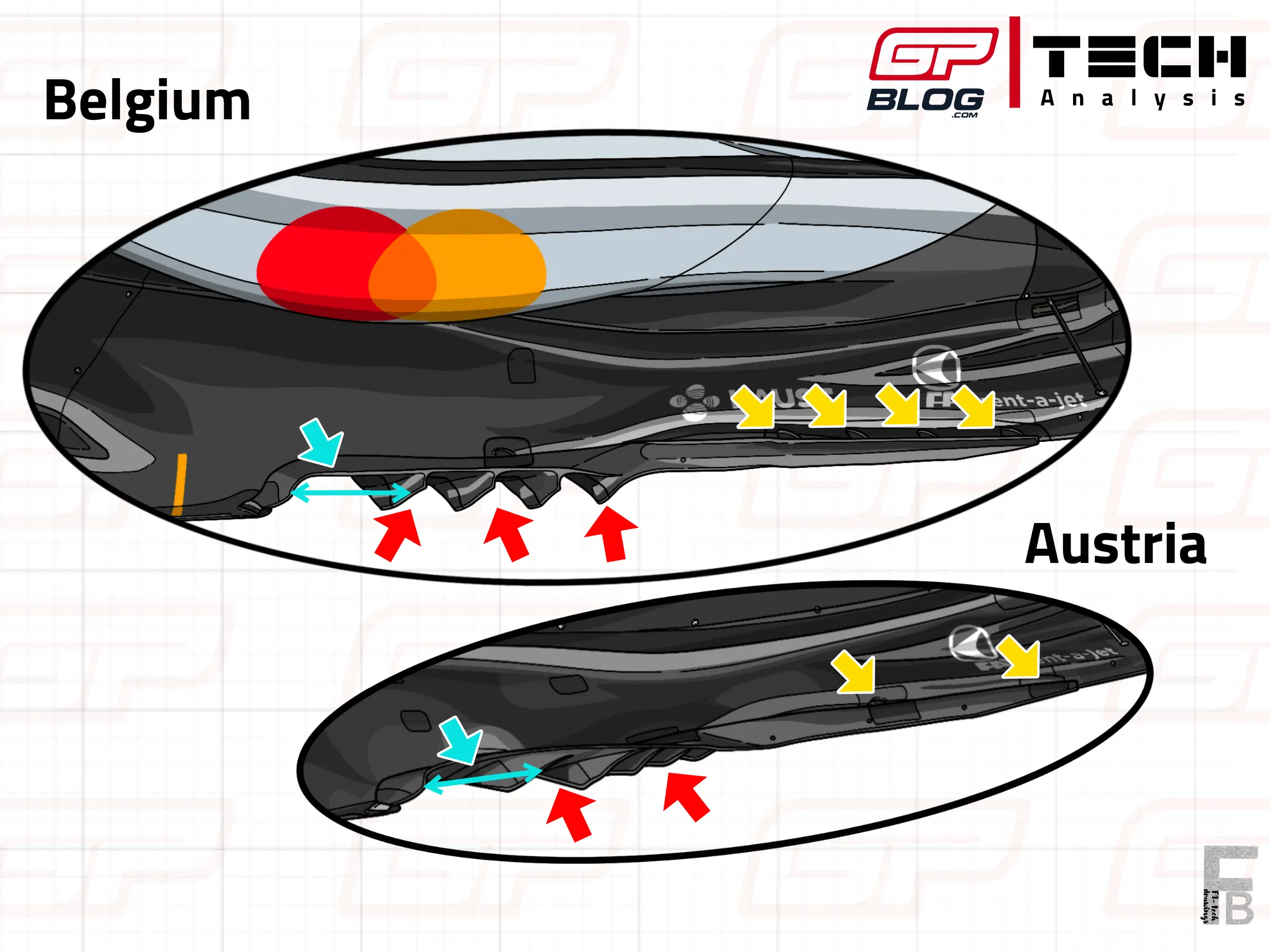

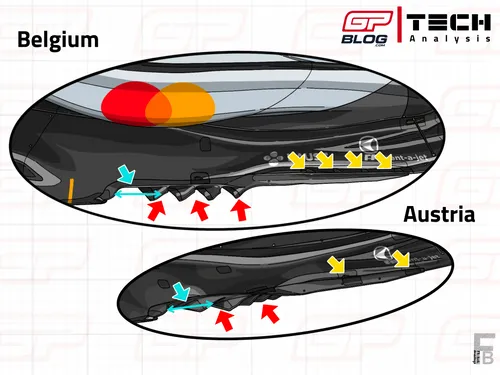

This rear wing choice, matched with the new floor introduced last time out in Spa-Francorchamps, immediately gave the MCL39 a boost compared to rivals: the car was much quicker than competitors’ cars in all the corners of the Hungaroring, proving to be able to generate a higher level of downforce from the Venturi channels. Moreover, the excellent stability of the aerodynamic platform allowed Norris and Piastri to push a lot in the last sector, characterised by two long corners, where a good balance between front and rear axle is required.

Last but not least, the great ability to keep tyre temperatures under control played in McLaren’s favour last weekend as well: over the single lap, the two MCL39s were the only cars that arrived at the last sector with still enough tyre to push through those long corners and set fastest sectors. This aspect once again proved the car’s great ability to babysit the tyres both during the single lap and the race pace sims, proving to be way ahead of the rest.

McLaren's new floor introduced in Spa-Francorchamps

This great competitiveness allowed Norris and Piastri to set a 1-2 in every practice session of the weekend, except for qualifying, where they struggled massively in Q3 due to the cooler asphalt temperature (from the beginning of Q1 to the end of Q3 the track temperature dropped of 16°C) and the wind, which unsettled their car producing visible understeering in slow corners.

Despite this minor unexpected event on Saturday, Norris and Piastri managed to get back to the top two positions during Sunday’s race: the first adopted a one-stop strategy, which worked beautifully thanks to an optimal tyre management of both the medium C4 and the hard C3. As Andrea Stella explained after the race, Norris was able to push the medium so far in the first stint (32 laps): “Lando found himself adopting a different strategy, and had cleaner air, allowing him to fully exploit the car's potential. When we decided on a single stop, we didn't think it was possible, but credit must be given to Lando, who set fast laps on relatively used tyres.”

As the Italian engineer explained, the Hungaroring’s asphalt offers good grip but low tyre stress, as the tyre degradation is mainly thermal. As a consequence, as the tyre wears, there’s less rubber on the shoulder and this inevitably gets colder, allowing the tyre itself to last longer than expected without facing big drops in lap times. It was this element, together with the MCL39’s ability to babysit the tyres like no car on the grid, that allowed Norris to make the one-stop strategy work while still pushing hard enough to prevent Piastri’s comeback.

Read also

What's behind Ferrari loss of performance?

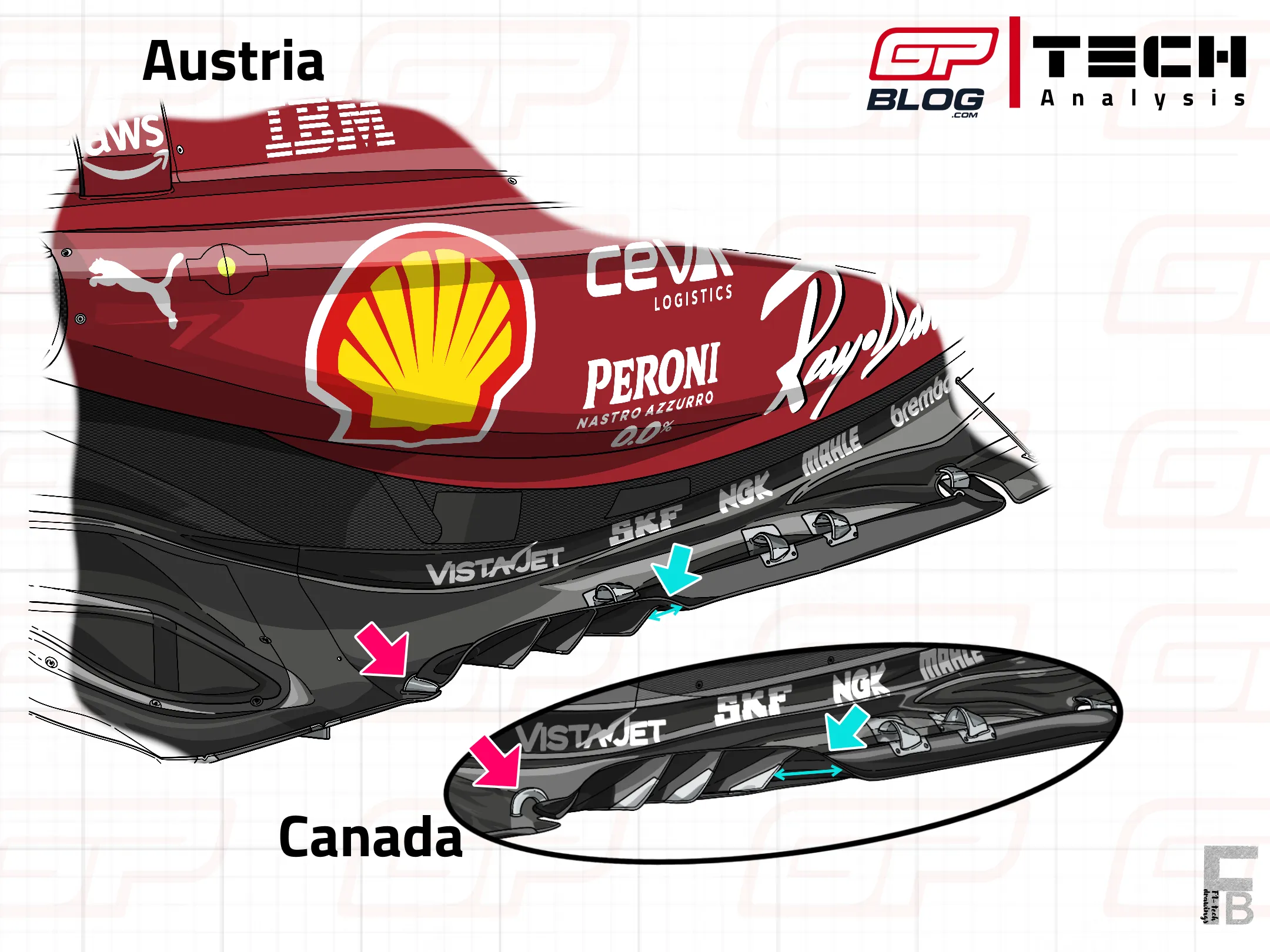

Ferrari had a very good weekend in terms of performance, proof that the rear suspension introduced at Spa-Francorchamps last weekend effectively worked, allowing engineers to run less extreme set-ups, making the car easier to drive and to push to the absolute limit, thus quicker.

Particularly interesting is how the engineers approached the weekend from a rear wing point of view: in FP1, Hamilton and Leclerc ran two different rear wing and beam wing versions, to gather data on which spec better suited the track and the two drivers’ driving style.

The main differences lay in the mainplane design: the rear wing version adopted by Leclerc was characterised by a mainplane with a shorter chord and with a relatively soft and curvilinear attachment to the endplates, aimed at minimising drag and maximising the efficiency of the wing profile itself (this rear wing spec was the same one used in Spain).

As for the version tested by Hamilton, it was a maximum-load version (used in Monaco) and featured a mainplane with a much higher chord than the version used by Leclerc and with a more angular connection to the endplate, precisely to maximise the downforce generated despite efficiency.

Leclerc's wing choice for the Grand Prix

As far as the beam wing design choice is concerned, the two drivers also adopted different specs: Hamilton ran the same version used in Monaco, while Leclerc ran the lower downforce version adopted in Barcelona.

The overall rear-end package fit on Leclerc’s car was a slightly lower downforce one, as it allowed the SF-25 to be the quickest car on the straights and through the first sector, proving to be very efficient. On the other hand, the setup tested on Hamilton’s car generated much more drag, but probably gave the 7-time World Champion a much more stable car on the rear end, which is exactly the element that gives him trouble in the corner entry phase.

After the tests made during first session, the team decided to make changes also on Hamilton’s car and adopt on both cars the same rear wing and beam wing used by Leclerc in FP1, as they represented an overall better choice, providing a good level of downforce in Sector 2 and 3, with a higher top speed compared to the MCL39’s one on the main straight.

Probably due to his driving style preferences, Hamilton wasn’t comfortable with the slightly unloaded rear end, forcing the team to come back to the rear wing and beam wing choice he made in FP1 from FP3 to the rest of the weekend. Despite the changes in terms of setup, the World Champion never seemed to find the right balance and performance, getting knocked out in Q2 in 12th place.

Lewis Hamilton in the Ferrari SF-25 at Hungary

On the other side of the garage things went much better with Leclerc who managed to get his first pole of the season also thanks to the set-up choices and the atypical conditions faced during Q3: the cooler track conditions and the different wind direction compared to Q1 and Q2 forced drivers to adapt quickly to the change of conditions and Leclerc is probably one of the best on the grid to be able to do so. Moreover, the cooler temps helped his SF-25 arrive in the last sector with much cooler tyres, allowing the Monegasque to push a little bit more despite free practices, where the high temperature made the rear soft tyres overheating during the lap, consequently arriving in Sector 3 with high temperatures and low grip, making him lose precious time compared to the two McLarens.

After the incredible performance, the Sunday’s race started perfectly for Leclerc, who managed to keep the lead during the whole first stint on the medium, when he was also able to push on the tyres without facing deg issues, opening the gap on Piastri to 3 seconds before the first pit stop. Already on the second stint on the hard it was pretty clear that the Australian driver had probably a bit more pace than the Ferrari, as he managed to stay within 2 seconds of Leclerc for the whole stint, proving the phenomenal McLaren’s tyre management already described above.

Lewis Hamilton during the Hungarian Grand Prix

It was, however, during the last stint that problems for Leclerc started to emerge: the Ferrari driver saddly started to lose almost 2 seconds per lap from Norris in front and Piastri behind, consequently losing the position not only to the Australian driver but also to Russell in P4, who was way further back at the beginning of the stint.

The significant and sudden lack of pace experienced only during the last stint was immediately attributed to some “chassis issues” by Ferrari and Leclerc himself after the race, even though there’s something mysterious about this problem. First of all, during the race, Leclerc’s engineer Brayn Bozzi never told him to have serious issues with the car (eventual chassis damage is something that only the engineer can see through live data) and Leclerc himself repeatedly complained to the team over the radio, saying that: “I can feel what we discussed before the race. We need to discuss those things before doing those. We’re going to lose the race with these things. We’re losing so much time.”

All these words seem to refer to something that is not as casual as a chassis eventual breakdown (something you can’t decide before the race), but on some aspects that were agreed before the race by the team and Leclerc himself: the tyre pressure or the ride height (which impacts on the plank wear during the race).

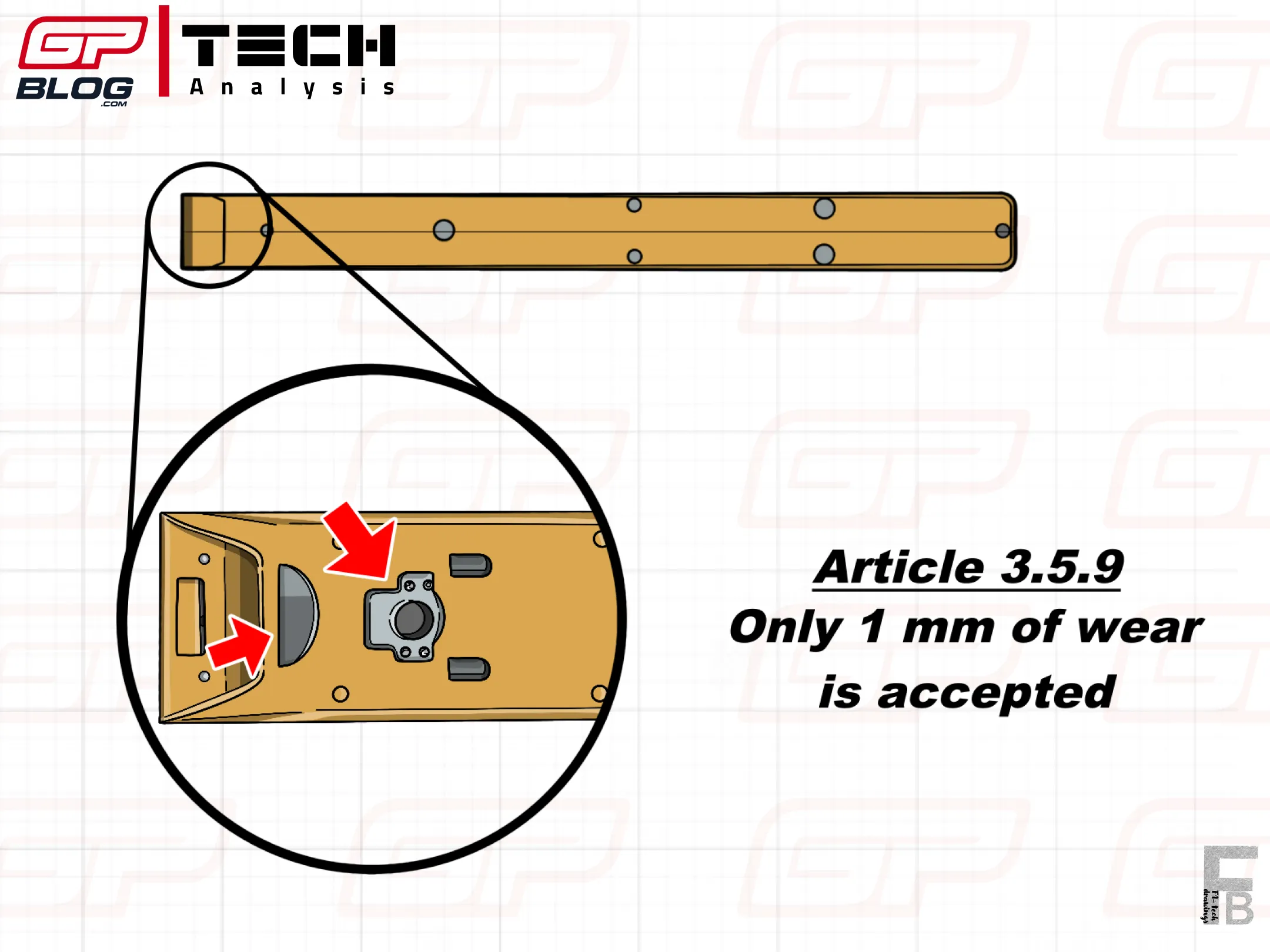

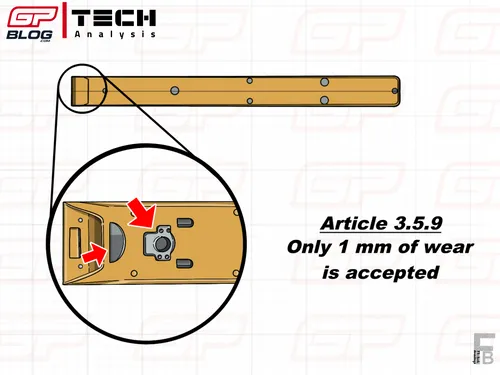

FIA rules on the plank wear during the race

The reason behind Leclerc’s loss of competitiveness likely stems from a combination of factors: to secure pole and improve performance, the team probably opted for a bold ride height choice, aware that they had little to lose compared to McLaren. Moreover, the SF-25 runs a pretty soft suspension set-up, to be much more competitive through slow speed corners and on those corners where kerbs need to be attacked. This decision effectively paid off on Saturday, enabling Leclerc to start from P1. However, the first stint on the mediums (with high fuel load, i.e. lower car in terms of ride height) where Leclerc pushed a lot, probably caused a bigger plank wear than the predictions and calculations made by the team.

As a consequence, Ferrari’s engineers may have decided to adopt higher pressures on the last set of hard tyres to improve the overall stiffness of the SF-25, allowing Leclerc to run in a more “safe zone” compared to the first two-thirds of the race. This led him to struggle with warming up the tyres, already losing time compared to McLaren during the first few laps after the stop. Moreover, to avoid a potential disqualification, he also had to slow down by almost 2 seconds, eventually losing the podium to George Russell and finishing the race in P4.

Leclerc and Norris after the race

A similar expiation to this issue was also give by Mercedes’ George Russell immediately after the race: “The only thing we can think of is they were running the car too low to the ground, and they had to increase the tyre pressures for the last stint because they were using an engine mode that was making the engine slower at the end of the straight, which is where you have the most amount of plank wear.”

Although the Briton’s point of view should be taken with a grain of salt, it’s clear that behind Leclerc’s poor performance in the third stint there’s more than just a problem to the chassis. Still, the ultimate proof will be the Dutch GP. If Ferrari decides to change Leclerc’s chassis in that occasion, then is probable that a all the theories previously explained are just nonsense, otherwise something previously explained may have effectively happened during the Hungarian Grand Prix.

Read also

Read more about:

Rumors

Popular on GPBlog

1

Williams end suspense with FW48 reveal: follow the launch event here

2883 times read

2

Confirmed: Ferrari poaches top engineer from within Red Bull family

2738 times read

3

F1 champion Jenson Button makes surprising move to Aston Martin

1079 times read

4

Wolff holds fire on W17 potential until Verstappen lays cards on the table

1078 times read

Loading